Back in 1999 I sat in the San Diego County Courthouse reading Seth Godin’s Permission Marketing, hoping that I didn’t get selected to serve on the class-action lawsuit against grocery chains who had allegedly conspired to fix prices on eggs.

I run hot and cold on Godin these days but Permission Marketing made a lot of sense and still does to a large extent. The core principle was that you needed permission to market to your customer.

Make the Permission Overt and Clear – Chapter 9, p 163.

As an early email marketer I recall the days when double opt-in lists were all the rage. Opt-in just wasn’t enough because the methods of collection could have been less than overt and clear. A double opt-in list ensured that you were getting the best list, the Glengarry list.

Opt-In versus Opt-Out

The difference between opt-in and opt-out can be substantial. Opt-in is the active choice to accept something, while opt-out is the passive acceptance of something. The problem here is that inertia can be quite powerful. The default presentation is often used by users as they seek to efficiently complete a task.

That’s not to say all opt-ins are created equal. The acceptance of terms of use (and privacy) before completing a download or registration is a weak opt-in since the majority of people don’t read it and those that do often don’t understand it. This type of coerced opt-in may be better than an opt-out but not by much.

Is Opt-Out Bad?

As a marketer, opt-in can be frustrating. A product or service that you just know would be valuable to a user is gated by their natural inertia. You run the numbers and it’s clear that an opt-out would be better for both the business and the user. Quite simply, you’d be able to deliver a valuable product to more of the right users. Those who don’t see that value can opt-out. No fuss, no muss right?

Well, permission marketing would tell you that you need overt and clear permission from a user to start that relationship. A user must raise their hand. Is opt-out overt enough? That’s debatable but it brings us to another permission marketing principle. Once given permission, you can’t abuse that permission. That’s where things have gone awry.

Opt-out got a bad name because (way) too many businesses abused that weak permission by not being relevant. It’s a shame since a good marketer could probably pull off an opt-out program. And that’s just what Facebook and Google are doing.

Value and Relevance

The value of your product or service and the relevance you deliver to the user are going to be paramount to maintaining that permission, no matter how it was attained. Think about that for a minute.

What I’m saying is that if your product or service is that good, you can acquire those customers in nearly any way. Opt-in, Opt-out, Optimus Prime, it won’t matter. Sure, some people will claim it does, but there’s evidence to the contrary.

Google is Good … Enough

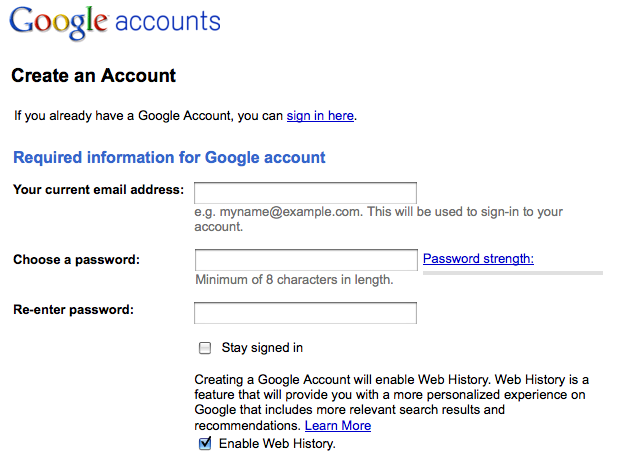

Google tracks and uses your search and site history to personalize your search results. They actually do this when you’re signed-in and signed-out. Here’s a look at how you sign up for Web History.

It’s opt-out and it’s relatively overt, but is it clear? It communicates the benefits quite nicely but what the feature actually does … not so much. But hey, that’s why there’s a Learn More link, right?

Web History actually can make your Google experience better. For most users I’d guess the Web History feature is completely transparent and they have no idea that their actions are being recorded. They simply think Google works great.

But what happens when someone figures out what’s going on?

What People Say and What People Do

People may say they would turn Web History off but how many really do? Sure, sometimes there’s a meme that takes hold and a few folks will very publicly call it quits. But the majority don’t … even when they say they will. The bark is much worse than the bite. And both Google and Facebook know it.

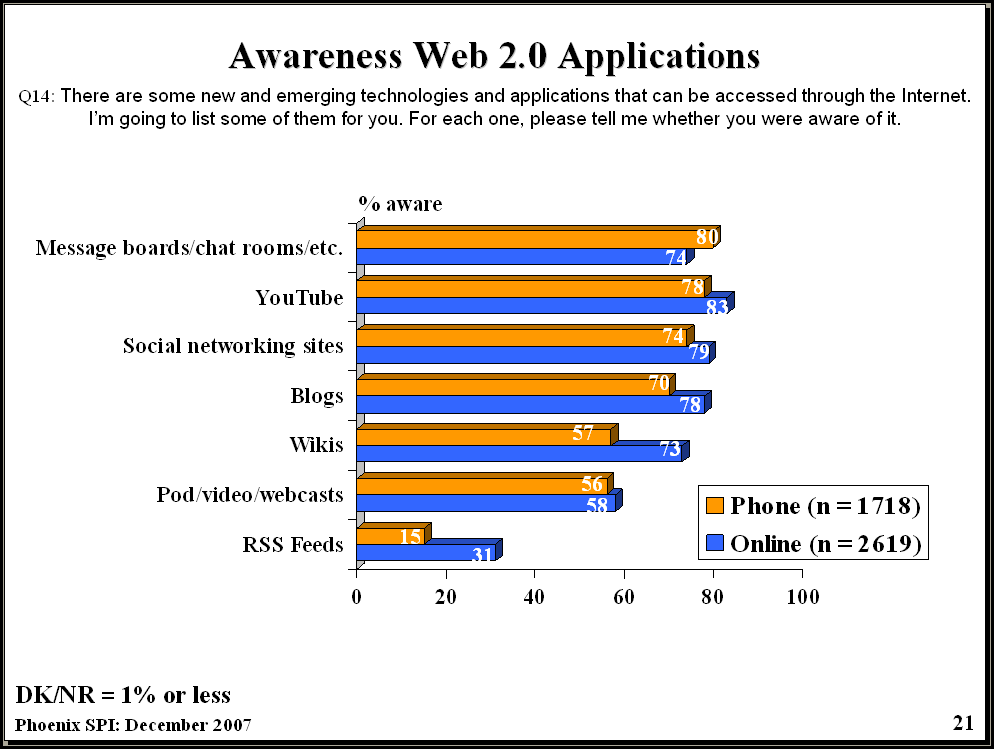

Lets take behavioral targeting (BT) as an example.

Behavioral targeting uses information collected on an individual’s web-browsing behavior, such as the pages they have visited or the searches they have made, to select which advertisements to display to that individual.

When people are asked whether they want this type of advertising, the response is generally negative.

Yet, behavioral targeting has proven to be very successful with click through rates substantially higher, often cited at three times the normal click through rate and recently noted in one study (pdf) as having the ability to achieve a 1000% lift. The ads are more relevant and people are voting with their clicks.

Google’s DoubleClick has a BT program. They call it interest-based advertising. The program is opt-out and Matt Cutts recently commented on the opt-out behavior.

Only a relatively small number of people visit that opt-out page each week, and the majority of them change their interests rather than opting out.

Once again, we see a product delivering enough value and certainly enough relevance to overcome any ire users might have about the ‘auto’ opt-in. In fact, the product produces such relevance (as seen by the high CTR) that most users simply think the ads are getting better. They’re not giving much thought to the how, just that it’s a better experience.

What about Privacy?

I still believe in privacy. I actually have Web History turned off and I don’t share much on Facebook. I consciously made those choices. Just like I make the choice not to give my name and address away at the drop of a hat to enter to win the new car parked in the middle of the mall. There’s a certain level of personal responsibility and common sense that must be levied on the user.

I believe that you would see users opt-out of these services if they didn’t provide the requisite relevance and value. Right now, Google and Facebook do for the majority of users.

Marketing Privacy

Google has been careful, outside of Buzz, to not provoke negative user interest. Instead, they’ve worked and publicized their attempts to make opt-out and privacy settings more available. Why? They’ve seen that users are willing to give up a certain amount of privacy to engage in their products. So they’re happy to have 100,000 people a day visit their dashboard.

Facebook, on the other hand, has provoked negative user interest. They make broad sweeping changes that highlight the exchange of privacy for value. Coupled with a poor user interface for the various opt-out settings and Facebook has caught substantially more flak.

Google has been marketing privacy while Facebook has been marketing value.

Intravenous Permission

Have Google and Facebook killed Permission Marketing? Not really. Google, and Facebook to a lesser degree, has short-circuited the natural progression of permission and achieved a type of intravenous permission (the highest level) through the release of great and free products. (Free is important. It creates a subtle user obligation.)

Users can always revoke this level of permission. It will take a break in trust, an abuse of permission, to force users to evaluate their exchange of privacy for value. Even then, that balance will have to be substantially different for users to make a change.